“Bottom-up processing” is a term used to describe how the human nervous system detects signals and salience, but has not yet begun to extrapolate meaning from the data. After the senses gather and roughly organize the data, the brain begins to examine the information, which provides a meaningful interpretation of what is being sensed. This interpretation is aided by prior knowledge and is known as “top-down processing”. The prior knowledge that enables humans to understand a stimulus event is based on past experience that is stored in long-term memory (Wickens, Lee, Liu, & Becker, 2004, pp. 121, 125). The human brain can perform top-down processing quickly and effectively because it is highly organized, interconnected, and constantly evolving. Humans use conceptual structures to guide cognitive processes. Understanding a person’s mental models enable designers to predict how a person will interact with a product that a user has used before or has never seen -- this paper will examine the mental model of a person using a first-generation iPod for the first time.

Types of Conceptual Models

Humans want to understand everything, which leads us to look for causes of events and properties of objects so that we can form explanations. When we find a cause-and-effect chain or a list of properties that makes sense, we store them as a conceptual model for understanding future events or objects. These conceptual models are essential to understanding our experiences, predicting the outcomes of our actions, and handling unexpected occurrences (Norman, 2013, p. 57). Semantic knowledge is knowledge of the basic meaning of things, so human knowledge is organized into semantic networks where related pieces of information share related nodes and sections of the network (Wickens et al., 2004, p. 136).

A schema is one type of conceptual structure which makes it possible to identify objects and events (D’Andrade, 1992, p. 28). Simply stated, a schema is “a general knowledge structure used for understanding” (An, 2013). Schemas are stored in long-term memory as organized collections that are quickly accessible and flexible in application (Kleider, Pezdek, Goldinger, & Kirk, 2008). The general cognitive framework of a schema provides structure and meaning to social situations and provides a guide for interpreting information, actions, and expectations (Gioia & Poole, 1984).

Schemas about events are known as scripts (Kleider et al., 2008). Scripts are the most behaviorally oriented schemas, and are mental representations of sequences and events (Sims & Lorenzi, 1992, p.237). Script behaviors and sequences are appropriate for specific situations, ranging from the tasks required to tie one’s shoes to the expected “performances” in social situations, such as going to a restaurant, attending lectures, or visiting doctors (Gioia & Poole, 1984). Scripted behavior can be performed unconsciously, although active cognition is required during script development or when a person encounters unconventional situations (Gioia & Poole, 1984).

Mental models are schemas about equipment or systems (Wickens et al., 2004, p. 137). Mental models describe system features and assist in controlling and understanding a system. Mental models can begin as incomplete, inaccurate, and unstable, but become richer as a user gains experience interacting with a system (Thatcher & Greyling, 1998).

Highly Organized

Semantic networks, schema, scripts, and mental models are highly organized, and schemas are organized within a hierarchy (D’Andrade, 1992, p. 30). The conceptual systems and mental models in the mind are extensive, distributed throughout the brain, and organized categorically (Barsalou, 2008). Semantic networks have much in common with databases or file cabinets, where items are stored near related information that are then linked to other groups of associated information (Wickens et al., 2004, p. 136). Conceptual systems categorize settings, events, objects, agents, actions, and mental states (Barsalou, 2008). Mental models categorize information to create distinct sets of possibilities based on what a person believes to be true (Johnson-Laird, 2013).

Interconnected

The power of human mind is not in its capacity but in its flexibility -- most new concepts are made by assimilating minor differences into existing knowledge (Ware, 2012, p. 386). The conceptual system includes knowledge about all aspects of experience, including settings, events, objects, agents, actions, affective states, and mental states (Barsalou, 2008). Prior knowledge facilitates the processing of new incoming information because it provides a structure into which the new information can be integrated (Brod, Werkle-Bergner, & Shing, 2013).

The mind groups or “chunks” large numbers of attributes into a single gestalt. For example the configurational attribute of “dogginess” is a configuration of many individual recoded attributes, such as nose, tail, fur, and bark. A collie is a kind of dog, so a collie inherits all of the attributes included in chunked quality “dogginess” (D’Andrade, 1993, p. 93). The networked nature of prior knowledge means that once a concept is activated, then other related concepts become partially activated, or primed (Ware, 2012, p.386). The strongly interconnected pattern of elements can be activated with minimal input (D’Andrade, 1992, p. 29), and conceptual systems generate anticipatory inferences (Barsalou, 2008).

Constantly Evolving

The brain is not like a camera that captures and collects holistic images. Instead the conceptual system is a collection of category knowledge that contains a powerful attentional system that focuses on individual components of experience and establishes categorical knowledge about them (Barsalou, 2003, 2008). New information is consolidated into long-term memory when the mind actively processes the new information to integrate it with existing knowledge (Craik, 2002). Whenever the mind focuses selective attention consistently on components of experience, the mind develops knowledge of the category (Barsalou, 2003). Knowledge is constantly being accumulated because the mind is constantly detecting regularities in the environment (Brod et al., 2013). For example, when the mind focuses on a blue patch of color, the information is extracted and stored with previous memories of blue, which adds to the categorical knowledge of “blue.” Over time, the mind accumulates a myriad of memories in a similar manner for objects, events, locations, times, roles, and so forth (Barsalou, 2003). The mind develops complex concepts such as relations (e.g., above), physical events (e.g., carry), and social events (e.g., convince) through the same mechanism (Barsalou, 2008).

Categorization

Humans categorize all objects and events we encounter in the world. Categorization is essential for survival -- if you mistake a stove for a chair or tiger for a housecat, the consequence may be disastrous. Because of this survival need, the categorization of objects and events takes places unconsciously (Vecses & Koller, 2006, p. 17). As people process members of a category, they store a memory of each categorization event. When encountering future objects or events, people retrieve these memories, assess their similarity, and include the entity in the category if there is sufficient similarity (Barsalou, 1998). Categorical knowledge provides rich inferences that enable expertise about the world — rather than starting from scratch when interacting with something, a person can benefit from knowledge of previous category members (Barsalou, 2003).

Three models for categorizing objects and events are the exemplar, prototype, and classical models. In the exemplar model, people’s representation of an object is a loose collection of exemplar memories, and to categorize an entity, a person attempts to find the exemplar memory that is most similar to the entity. In the prototype model, a person extracts properties that are representative of a category’s exemplars and integrates them into a category prototype. In the classical model, an entity must meet certain rules to qualify for membership (Barsalou, 1992, pp. 26-29).

Affordances

People interpret and categorize entities to determine if they can operate on their environment (Ware, 2012, p. 18). People perceive not only features of objects, but also information about how to interact with them (Apel, Cangelosi, Ellis, Goslin, & Fischer, 2012). The term “affordances” describes perceived possibilities for action offered by objects. A cup, for example can be used for drinking or it can be used for catching a spider — a cup affords both of these actions (Humphreys, 2001). Affordance is not a property of an object, but a relationship that depends on the object, the environment, and the agent’s mental models (Norman, 2013, p. 11).

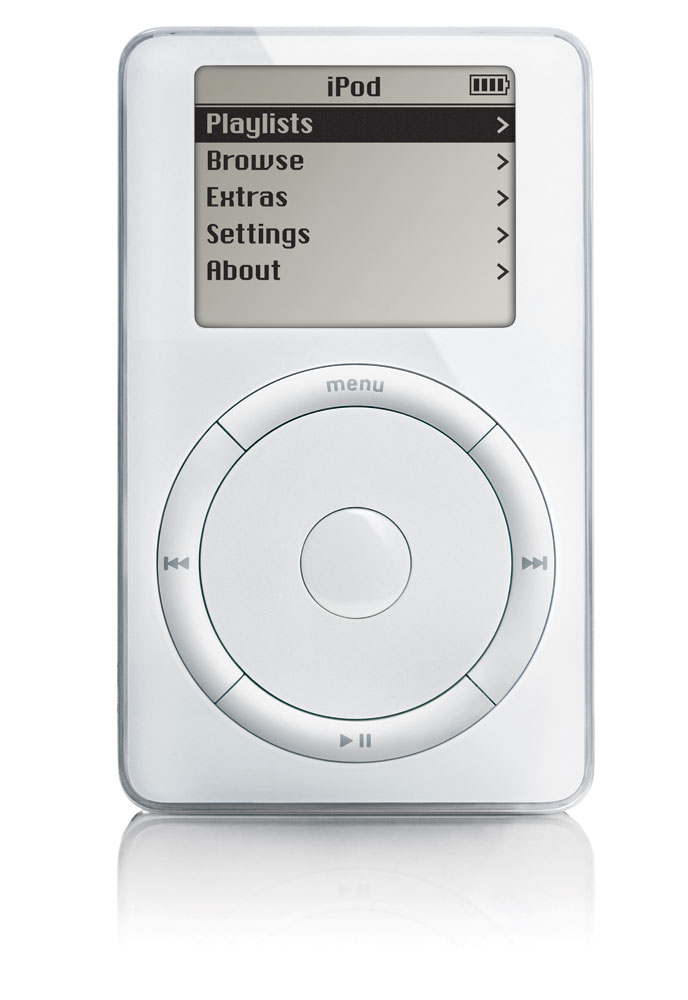

Case Study - First Generation iPod

Apple released the iPod on Oct 23, 2001. Before the iPod, the mass consumer market was familiar with portable music players in the form of cassette players, CD players, and MP3 players (images in Appendix 1). Sony’s Walkman cassette player was released in 1980 and featured buttons for play, stop, fast-forward, rewind, open, and a slider for volume. Sony introduced the Discman in 1984 and it featured buttons for play/pause, next song, previous song, stop, play mode, repeat/enter, open, and a slider for volume. The first commercially successful MP3 player was the Diamond Rio introduced in 1998, which featured buttons for play/pause, stop, next track, previous track, volume up, volume down, random, repeat, A-B, and hold.